Welcome to the U-M Library’s digital magazine, which highlights stories from around the library, the library in the news, and upcoming events. A new edition is published at the start of each fall and winter term.

Watch

The 1938 radio broadcast of "The War of the Worlds" by a young Orson Welles sparked widespread panic among listeners who believed the fictional alien invasion was real.

Or did it?

TranscriptSpeaker 1:

If an item doesn't appear in our records, it does not exist.

Speaker 2:

I've never seen so many books in all my life.

Speaker 3:

Get back to the library.

Speaker 4:

You're right. No human being would stack books like this.

Speaker 2:

What do you want to take out?

Speaker 3:

The librarian.

Speaker 1:

Shhh. Quiet please.

Joe Linstroth:

Welcome back to the University of Michigan library podcast. I'm Joe Linstroth. A few times a year we put these together to shine a spotlight on some of the amazing work being done by U of M librarians. For this episode we're going to head over to the Screen Arts Mavericks and Makers collection. That's the trove of notes, letters, photos and other primary source treasures that belong to such notable American filmmakers as Robert Altman, John Sayles, and Orson Welles. That's also where a really fascinating project hit a big milestone recently. After years of work, Phil Hallman, the collection's curator, and his team, have managed to turn some of the materials from the Orson Welles archive into a lesson plan for high school teachers, and last spring they gave it a test run. Teacher Karl Sikkenga and his class of ninth and tenth graders were the guinea pigs.

Karl Sikkenga:

Almost without exception, kids will come up with thoughts and observations and questions that never occurred to me, and I think that's a great way to use this kind of source.

Joe Linstroth:

We'll hear more about the lesson from Karl later, but first, it's worth retracing the long winding path the project has taken to get to this point. You may recall, there was a lot of publicity around the collection’s Orson Welles archives a few years ago. It started in earnest in 2013, which marked the 75th anniversary of Welles's historic radio broadcast of the H.G. Wells novel, The War of the Worlds.

Speaker 7:

Ladies and gentlemen, we interrupt our program of dance music to bring you a special bulletin from the Intercontinental Radio News. At 20 minutes before eight, central time, Professor Farrell of the Mount Jennings Observatory, Chicago, Illinois, reports observing several explosions of incandescent gas, occurring at regular intervals on the planet Mars. The spectroscope indicates the gas to be hydrogen and moving toward the Earth with enormous velocity. Professor Pierson, of the Observatory at Princeton, confirms Farrell's observations and describes the phenomenon as (quote) like a jet of blue flames shot from a gun (unquote). We now return you to the music of Ramón Raquello playing for you in the Meridian Room of the Park Plaza Hotel, situated in downtown New York.

Joe Linstroth:

The broadcast was so realistic in its depiction of an alien invasion, that it supposedly scared the bejeebers out of a country that was already jittery at the prospect of another World War. Newspapers reported mass panic, and the next day, Halloween 1938, a young Orson Welles faced a scrum of reporters who demanded that he explain himself.

Orson Welles:

I'm surprised that the H.G. Wells classic, which is the original for many fantasies about invasions by mythical monsters from the planet Mars, I'm extremely surprised to learn that a story which has become familiar to children, through the medium of comic strips, and many succeeding novels and adventure stories, should've had such an immediate and profound effect upon radio listeners.

Joe Linstroth:

But those reporters and the headlines and the history books got it wrong. There was no mass hysteria, and we know that now, thanks to some overlooked boxes of letters in a library’s Orson Welles archive. What was in those letters, which were written by listeners in 1938, right after the broadcast aired, told a very different story. One that would lead to a Michigan undergraduate student turning his honors thesis into a book and then into a PBS episode of American Experience. Here's Phil Hallman.

Phil Hallman:

There's a particular narrative that we think is the truth, but the letters show something different. So what's fascinating is that an undergraduate can go into this archive and explore it and come up with new material, and new research that people didn't necessarily know already.

Joe Linstroth:

The undergraduates name is A. Brad Schwartz. I called Brad, in Princeton New Jersey where he's now working on his doctorate in American history, to find out how this all started.

Joe Linstroth:

Tell me how you first discovered the some 1300 letters from listeners of Orson Welles's War of the Worlds broadcast? How did you come to find out about this trove?

Brad Schwartz:

It was all thanks to a U of M librarian named Phil Hallman, who curates the, what they call the Mavericks and Makers collection. I was taking a film course, it was Classical Film Theory, and one day Phil came in to give a presentation about all of the library resources that we students could use to write our final papers. And then he segued into this Orson Welles archive, and Phil specifically mentioned that we had all of these letters that were sent to Welles in response to The War of the Worlds broadcast, and that nobody had gone through them, really, in 70 years at that point, and so they just hadn't been explored. There was this sense that our understanding of Welles, and particularly this major event in media history was ripe for being reimagined.

Joe Linstroth:

So what did you find when you first put eyes on this collection? You said that Phil had told you many of them hadn't even been looked at.

Brad Schwartz:

I first went up to the Special Collections Reading Room in Hatcher, around February of 2011, and my first thought as soon as Phil described the collection was that there would be all these sorts of letters about people describing panicked reactions, about fleeing their homes, or loading a shotgun, trying to fortify themselves against the gas raid, all of the stuff that we're sort of familiar with through popular culture. And so I requested the boxes, boxes 23 and 24, if memory serves, and they're organized by state, and so, being from Michigan, born and raised and educated, I decided to pull the Michigan folder first just to see.

Brad Schwartz:

And I remember flipping open and the first letter was on stationary, I think from the U of M Union in Ann Arbor, but it was a letter from somebody writing to support Orson Wells, who had not been frightened, and who was sort of afraid that Welles might be punished or taken off the air. Now that's interesting, then I flipped to another letter, also from Ann Arbor as I recall, also from the University of Michigan, and also from somebody who had not been frightened, and who was again writing in support of Orson Welles and sort of to praise him, not to bury him. And I had to go through several letters before I found one of the ones that I was expecting, from somebody who had been frightened, and fled and all of that, but I was very quickly getting the sense that the panicked reaction that had been described was a gross exaggeration, that it was obscuring a larger phenomenon at work here.

Brad Schwartz:

The actual response to the broadcast was much more complex and much less overtly hysterical than pop culture has led us to believe, and by the time I had gone through not just Michigan but several other states worth of letters, just to feel around, get a sense of what was in there, I realized I had more than I had certainly bargained for, but at least I had a great project.

Joe Linstroth:

And he was right. Brad eventually published a book titled Broadcast Hysteria, Orson Welles's War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News. The book came out just in time for what would have been Orson Welles's 100th birthday in May of 2015. I mention the date because that was before the term fake news came to take on the meaning we think of today. Here's Brad again.

Brad Schwartz:

About a month after my book came out, Donald Trump announced he was running for president and fake news very quickly took on this different connotation, and a lot of what I saw in the letters and what I talked about in the book, about what do you do when the media can lie more convincingly than it can tell the truth? What is the responsibility that journalism has to convey different sides of the story? Those sorts of things that I was engaging with, with regards to War of the Worlds suddenly became so much more relevant.

Joe Linstroth:

Based on his work, Schwartz was also invited by PBS to co-write that episode of The American Experience to commemorate the broadcast’s 75th anniversary, and that's when the idea for the project emerged. Here's U of M librarian Phil Hallman again.

Phil Hallman:

Following the broadcast of the PBS documentary that Brad helped to write, I received emails from people asking me, could they have access to these letters, so it's an audience that I never connected to, but it dawned on me, and I thought, wow, this is an opportunity to reach an audience who's expressing desire to have it, and let's see what we can make happen.

Joe Linstroth:

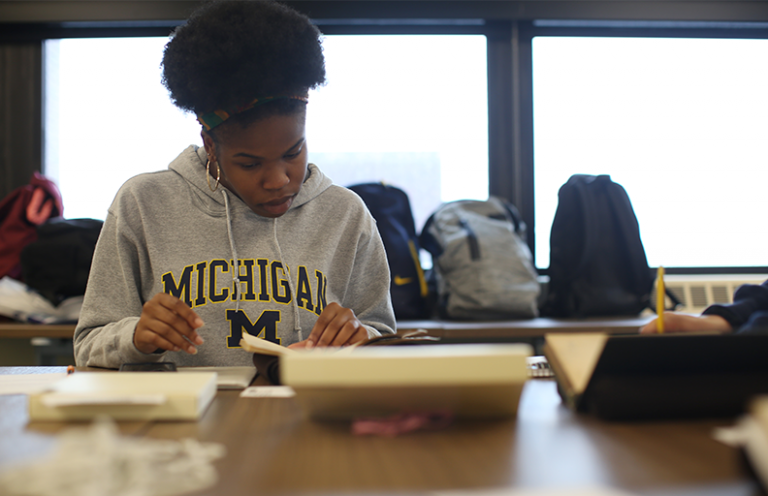

Many of the emails Hallman got were from high school teachers all across the country who wanted to use these letters in their classrooms, so he assembled a team and got to work. The goal was not just to make the more than 1300 letters available to the public online, the team went a step further and incorporated these letters into an actual lesson plan that teachers can use. Hallman and Vincent Longo who is a doctoral candidate in U of M's department of film television and media, and who has been working on a project, join me to talk about what they've been up to for the last three years.

Joe Linstroth:

Vincent, first describe the process. What are you doing with these letters?

Vincent Longo:

Sure, so our collection has over 1300 letters that were written to Welles, after the broadcast, and what we're physically doing is making high-resolution scans of them, putting them onto a digital database, and then making them fully word searchable, sortable, so that people can look through them in a variety of ways. We're also transcribing all of them, so we are both, when they are handwritten and when they are typeset, we are making sure that, either digitally or manually, we're making sure that people have the text itself.

Joe Linstroth:

How big of a lift has this been?

Vincent Longo:

It's a labor of love that we've been doing for three years, and scanning one letter takes about 15 minutes or so. Usually it's very high-resolution, so you just watch the scanner go slowly through. Phil has done a bunch, I've done a little bit, we've commissioned one class that worked on it for a semester, and now we have three other students who do it part-time, so even with that we're only about a little bit more than halfway.

Joe Linstroth:

What have been the biggest challenges that you've encountered so far, Phil?

Phil Hallman:

Well I think for me, it's just finding the easiest access for people to get to it. So we struggled with trying to figure out how it would be stored, because it's a lot of data, and we wanted it to be available through a website, but not all websites can handle the storage capacity, so we really struggled to find a compatible resource. So actually we've cheated a little bit, and we've sort of married two things together, and Vince might talk about that.

Vincent Longo:

Right, yeah, it's also about functionality, so how do you interact with an archival document? You know, ideally we'd want users to have an experience if they go to the archive, to look at the physical material, with a digital copy that's not possible, so a lot of websites that are really clean, like even ones like WordPress, or just a very generic website, you don't have that functionality of even zooming or really word searching effectively in transcribed text. So what Phil is talking about is we sort of cheated, we're sort of marrying the two together. We're going to have what we call a sort of a front page, which is more or less like a regular website, which will house the teaching material, overviews about the historical period and things like that, and then the back end is a much more traditional archival database. So you think of a bunch of search functions, from search by state, et cetera, you also think of thumbnails, where people can see the letters and click them, and then it opens up into its own screen, which you can then zoom in, zoom out, read, yep.

Phil Hallman:

You know a part of that, as Vince was saying, is to really kind of as best we can recreate the experience of being in the physical room with these physical objects, and the letters are arranged by state, so we want to be able to recreate that to some degree, as opposed to just sort of doing a word search for the average user. There's nothing wrong with that, but it's just a different sort of reaction you have to the physical object when you're doing a keyword search as opposed to physically handling something. It does something different to your brain. I can't quite explain it, but there's a different sensation of learning as well, so we wanted to try to create that as best we can. There's no way we can 100 percent recreate a physical experience, but that was the goal.

Joe Linstroth: In addition to scanning these documents and making them publicly available, you've taken it another step and you've created lesson plans for teachers to access if they want to use the materials in the classroom. You've done a test run of a lesson plan in a high school classroom last spring. What did you learn? Vincent?

Vincent Longo:

Well we learned that the students are really invested and interested in history. That was the first thing. My first worry in this was that they were going to say, oh, these old letters, who needs them, but the students really found them interesting. I think what's really cool about this project is that not only is The War of the Worlds story interesting in terms of broadcasting censorship issues, but it's also a local history on almost every level across the United States. So even if a student doesn't understand issues of liveness or scaring the country, they say, okay, well, this impacted Michigan, and we can clearly see that from the five or ten letters we gave to the students. So they said, wow, this person heard this broadcast in my home state, probably likely in their home city, and they said this mattered to them, so even just understanding local history, they can access it through that way.

Joe Linstroth:

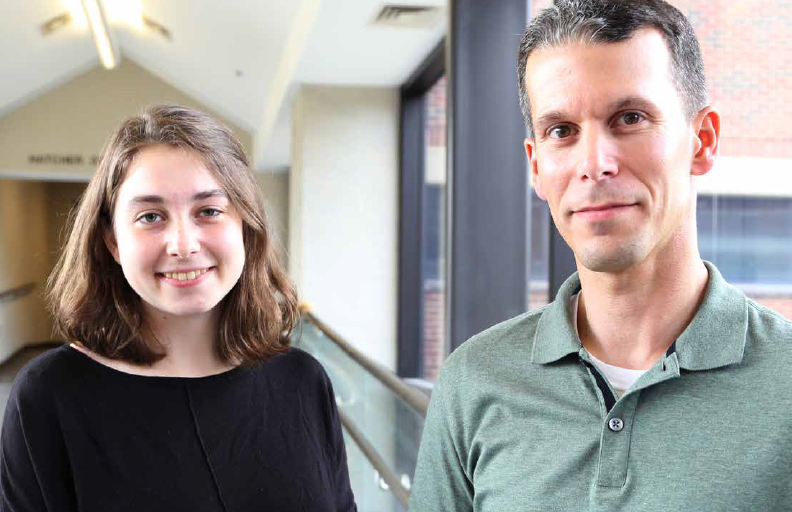

That was Phil Hallman and Vincent Longo. Just this past spring, Hallman, Longo, and their team, which also included Hope Shaffer and others, were finally ready to give their lesson plan a try. And they chose Karl Sikkenga’s classroom as the test site. Karl is an administrator at New School High in Plymouth, Michigan, where last year he taught American History to ninth and tenth graders. And he and I sat down to talk about how the class went.

Joe Linstroth:

How did the lesson plan fit into what you were already learning in the class?

Karl Sikkenga:

Well, it fit pretty seamlessly in about three different ways. One was that we use all kinds of primary sources. We try to look at history from many different perspectives rather than a conventional, kind of birds-eye view of the whole picture, so that's one thing. Another is having multiple sources about a single event, and so these primary sources that the library provided us with ranged from irate letters, to letters from school kids, to newspaper articles, to analyses, and we also used excerpts from the broadcast itself. And then the third piece is the way that media functions, in particular War of the Worlds, was important because it was a common experience that thousands of people were having simultaneously, and of course, in the present day, millions and millions of us have simultaneous experiences, but this was something that was really only being generated in that part of the century.

Joe Linstroth:

So you mentioned a number of materials that you used from The War of the Worlds collection. How did you use them?

Karl Sikkenga:

Well, we started with the broadcast without much preamble at all. I had said to the kids that we were going to be using a sort of imported lesson from the University with some materials that they were kind enough to provide to us, but without too much preamble, I simply played excerpts from the broadcast so that they could get some flavor for the experience in the moment.

Speaker 12:

I guess that's it. Yes, I guess that's the... thing directly in front of me, half buried in a vast pit. Must have struck with terrific force. The ground is covered with splinters of a tree that it must have struck on its way down. What I can see of the object itself doesn't look very much like a meteor, at least not the meteors I've seen. It looks more like a huge cylinder.

Karl Sikkenga:

Then I took four to six — I want to say it was about a half a dozen different sources — that they had provided again, the newspaper articles, the letters and so forth, divided the kids into groups, send them out, I want you to look at this one document, it won't take you long. Need you to make a couple of observations about it, and those could be more or less directed observations. Generally speaking, I try to give a little direction, but not very much. Almost without exception, kids will come up with thoughts and observations and questions that never occurred to me, and I think that's a great way to use this kind of source.

Joe Linstroth:

Is there something that comes to mind, on that regard, about a student or students that came up with something that wasn't in the lesson plan that struck you?

Karl Sikkenga:

Sure. Well, one of the letters is from a 13-year-old girl in Detroit, so a contemporary of these kids.

Joe Linstroth:

And let’s take a listen to that letter.

Speaker 13:

Dear Mr. Welles. In listening to your broadcast Sunday evening on Mercury Theater, I was one of the many listeners who believed things were really happening. However, I determined to hear it through. We were held entirely spellbound, until we heard, the Mercury Theater will continue in a moment, and did we have a laugh. I can truly say I do not care to listen to such a dramatization again, however you are certainly to be congratulated on such a realistic performance. Your play was the main topic of discussion in our English class today, and it’s for that I am writing to you. I would like a reply if possible. I am a girl, 13 years old in the eighth grade, and attend the Wilson Intermediate School. Your listener, Willa Young.

Joe Linstroth:

Now that was a pretty mature letter for a 13 year old.

Karl Sikkenga:

I can think of three or four comments they made on this letter alone that I would never have anticipated. Among them, "Wow, they really taught penmanship in that era." That was one thing that all the kids had something to say about. Another was, my kids, I remember a couple in particular, were impressed with the nuanced nature of her response, that she wasn't spouting about how angry she was, and how terrified and how unfair it was, she wasn't just saying wow you did a great job, and I liked the fact that my kids were sensitive to the degree of subtlety that a 13-year-old girl had, with which she had observed and analyzed the experience.

Joe Linstroth:

Was there a part of The War of the Worlds broadcast itself, you said you played excerpts, that students really responded to?

Karl Sikkenga:

There was a moment where he was, Welles was taking a remote report from a reporter in the field, and the reporters contribution sort of devolved into screaming and then it was cut off and there was a high-pitched hum. They were pretty gobsmacked by that. That was good stuff.

Speaker 14:

Good Lord, they're turning into flame!

Speaker 15:

Ahhh.

Speaker 14:

Now the whole fields caught fire. The woods... the barns... the gas tanks of automobiles... it's spreading everywhere. It's coming this way. About 20 yards to my right...

Joe Linstroth:

How did you connect The War of the Worlds, and the public's response, to what's going on in today's world for the students?

Karl Sikkenga:

Well I took a cue for that from the library folks, from the lesson plan that they had designed. They were interested in the exploration of fake news. I like to use a model called defend both statements, where in this event I might have said, okay defend both statements. The War of the Worlds broadcast was symbolically important regarding media in the United States. The War of the Worlds broadcast was really not very important. Anyone could defend either one of those statements.

Joe Linstroth:

Sure.

Karl Sikkenga:

And what my students get accustomed to doing, is my saying, I don't care what you actually think about this right now. I don't want you to tell me your opinion, everybody has opinions. I want you to explain why a reasonable person might argue either of these points. And the variety of materials, again that the library gave us, made it very easy for us to think about it in those terms.

Joe Linstroth:

Would you recommend The War of the Worlds archive to other teachers?

Karl Sikkenga:

Oh, heartily. You can't go wrong with it. You know, the worst thing that could happen is the kids don't think it's very interesting. That's not a disaster and it asks you to do all...

Joe Linstroth:

Teachers face those challenges quite frequently.

Karl Sikkenga:

I say that in school quite a bit, the worst thing that could happen here is that it’ll be a disaster, and we'll move on. And I will say, too, that I'm talking about a sort of conventional way to teach history, from the birds eye view, you know, seeing all the trends, seeing the movements from above almost, but increasingly, I think that the better textbooks and all of the better teachers are doing more than that, are doing more of this kind of work, and so I think that this kind of lesson is going to seem less and less unusual over time, and I think that's wonderful.

Joe Linstroth:

That was Karl Sikkenga, a teacher and administrator, at New School High in Plymouth, Michigan. So as we've heard, the project has come a long way since Brad Schwartz first cracked those boxes of unopened letters back in 2011. I asked Phil Hallman what he thought has made this project so different than any other he's worked on as a U of M librarian. Here's what he had to say.

Phil Hallman:

Well, for me it's about building a team effort, and normally I would just do this by myself as a curator, or I might work with a colleague, and we would do an exhibit or something along those lines, much smaller scale. But this is, as I said, we've done this for over three years now, and so each year we've added a new person to the team. We’re making appearances in local communities, so in addition to the school we visited, we recently went to Princeton, New Jersey, which was close to the site and the radio broadcast where the spaceship supposedly landed.

Joe Linstroth:

And this was a celebration of the 80th anniversary, we're on the 80th year.

Phil Hallman:

Yeah, exactly. And so, what's wonderful, is we're seeing legs to it. Usually when you develop something, you expect it to have a short shelf life, but this is something that I think is living beyond its expiration date. You know, it's really growing and continuing.

Joe Linstroth:

Hallman says he expects that this years-long labor of love will be finished by the fall of 2019. That's when he hopes to finally have all the letters digitized and available online for anyone who'd like to use them, including teachers. And that's a wrap for this edition of the U of M library podcast. A special thanks to Brad Schwartz, Phil Hallman, Vincent Longo, Hope Shaffer, Karl Sikkenga, and his daughter Evie Sikkenga, who read that letter for us. For more stories about what's happening at the library, check out the latest edition of our digital magazine, which is out now at magazine.lib.umich.edu. I'm Joe Linstroth, until next time.

Orson Welles:

So goodbye everybody, and remember please for the next day or so, the terrible lesson that you learned tonight. That grinning, glowing, globular invader of your living room is an inhabitant of the pumpkin patch, and if your doorbell rings and nobody's there, that was no Martian... it's Halloween.

Listen

Around the library

Immersive learning experiences

At the Shapiro Design Lab, located the first floor of the Shapiro Undergraduate Library, classes such as Sophia Brueckner’s Sci-Fi Prototyping and Lisa Nakamura’s The Internet is a Trash Fire have recently taken advantage of augmented, virtual and mixed reality (AVMR) systems to enhance conversation on course topics such as ethical tech design and online harassment.

The lab’s equipment, which is available by request and includes Oculus Rift, Google Cardboard, PlayStation VR, and Oculus Go, is intended for students, staff, and faculty who use games or other kinds of interactive/immersive experiences in their coursework and research.

More/LessIn Sara Blair’s How to Read Images class last semester, students visited the lab to examine a number of immersive VR/360° video experiences related to the Syrian civil war and refugee crisis.

“We’ve been especially interested in claims [that virtual reality is] a so-called ‘empathy machine,’ allowing users an apparently unmediated access to the experience of others,” says Blair, Patricia S. Yaeger Collegiate Professor of English Language and Literature. “Critics have been quick to point out that this is a fantasy that masks the appropriation of that experience, and the way in which it's being transformed as entertainment or spectacle.”

Part of what was exciting about access to the lab's technology, Blair says, is that students “were able to connect the promise of VR to the historical response we've studied of earlier new media forms — beginning with photography, whose original format, the daguerreotype, offered viewers the sense of a presence so immediate that it seemed to bring loved ones back from the dead … VR is just the latest in a long line of visual media that train us in complex ways of seeing our world, and make that training invisible.”

Prefer a more recreational use of the technology? The Computer and Video Game Archive in the basement of the Art, Architecture and Engineering Library on North Campus includes a Sony PlayStation VR reservable for play within the archive room.

— Emily Buckler

The girl with the library tattoo

The story of the girl with the library tattoo begins with the rescue of discarded U-M Library spirit wear.

Morgan Lindblad was leaving Festifall her freshman year when she noticed something on the ground. When she looked closer, she found temporary tattoos, navy blue and printed with the library logo. She picked them up and wore one to the next home football game; after an overwhelmingly positive response from her friends and those in the stands around her, a tradition was born.

More/LessWhen she started to run out of tattoos sophomore year, she returned to where it all began: Festifall. She happened across the library booth and asked if there were any tattoos, explaining her game day tradition. And while there weren’t any stocked at the booth, one of the staffers had some in her purse. She gave them to Lindblad, sustaining her for another season.

When she ran out again junior year, she knew she couldn’t just hope for the best. What started as a joke had become her thing, and repping the heart of academics at football games was symbolic. “I wear them on game days because it’s like, work hard, play hard — I think that’s very Michigan,” she said.

By this point, she wasn’t the only one invested in the library tattoos. She would be asked before each game if she’d be wearing the library tattoo. She would share tattoos with those around her. When friends found a U-M Library shirt at a local Goodwill, they bought it for her and insisted she wear it on game day. Lindblad even made the library face tattoo tradition a family affair, sharing one with her mom when she visited for a football game.

And then the crisis came, one that Lindblad documented on Instagram: She ran out of tattoos, and, this time, a library booth on the Diag didn't have any. But librarian Marna Clowney-Robinson, certain that someone, somewhere had some, offered to help. Lindblad and her Instagram followers waited for a week, in suspense. Clowney-Robinson found a stash and supplied Lindblad with at least enough to get her through her senior year season. She and the library tattoo fans celebrated.

As a junior majoring in Program in the Environment and minoring in biological anthropology, Lindblad spends her fair share of time studying. Her preferred study spots are Shapiro and the basement of Hatcher. “It’s a nice study place,” she said. “I definitely go to the library more than my own house, because I will fall asleep if I try to study in my own house.”

She works hard, and when her friends come to visit, she makes sure to introduce them to the library, which is with her even on football Saturdays as she plays hard.

Want to wear your love of the library for all to see? Get your own temporary tattoos from the Shapiro circulation desk or the Art, Architecture & Engineering Library on the second floor of the Duderstadt Center.

— Danielle Colburn

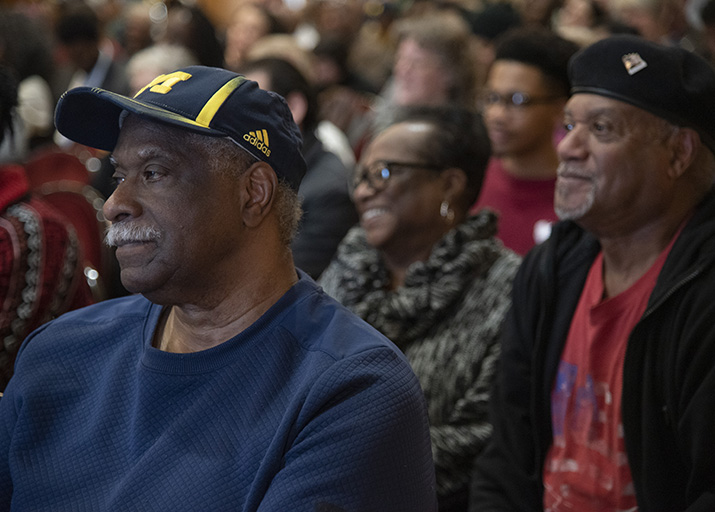

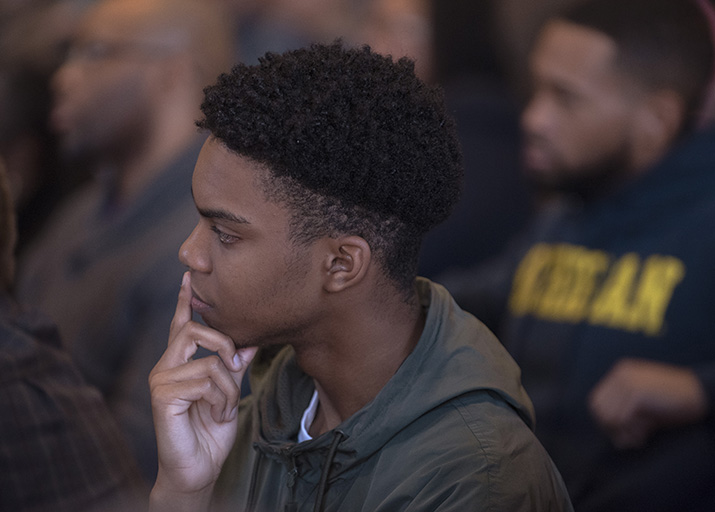

MLK Day at the library

Michael Eric Dyson captivated the audience with his talk, Martin Luther King Jr. and African-American Leadership in the 21st Century.

Dyson's talk was part of the annual U-M Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Symposium.

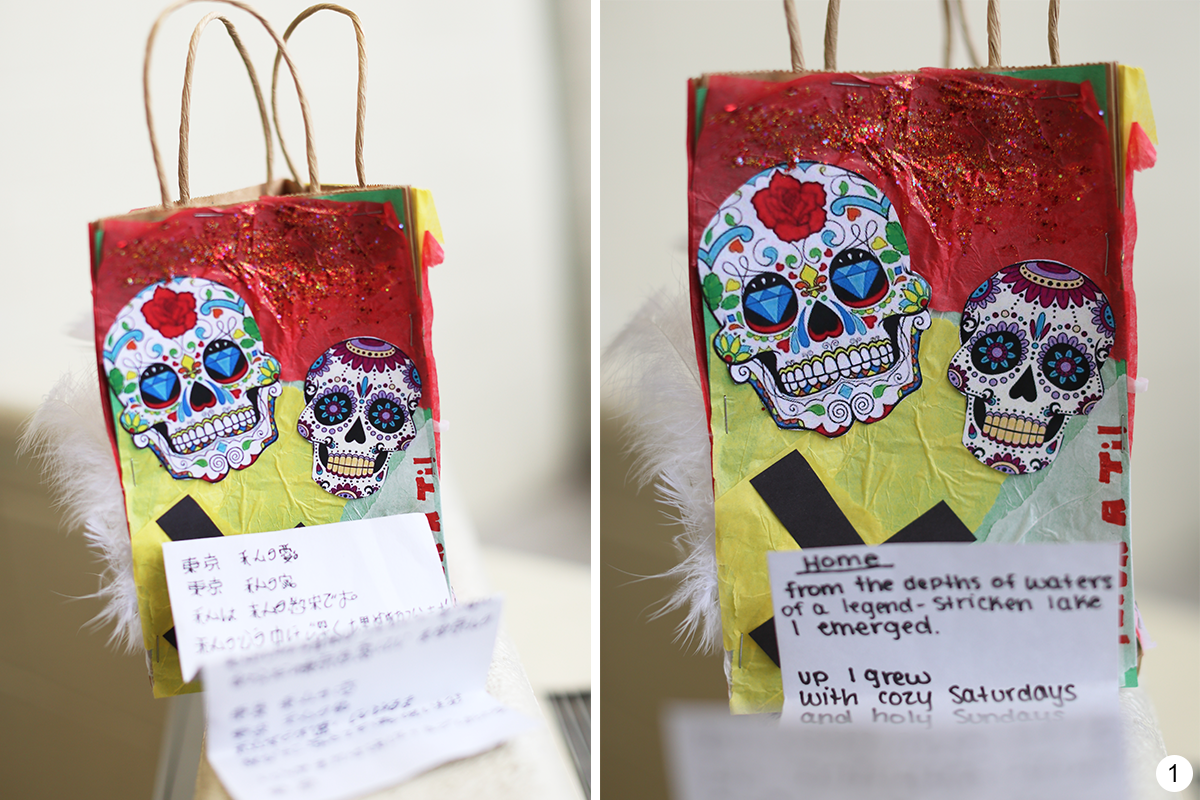

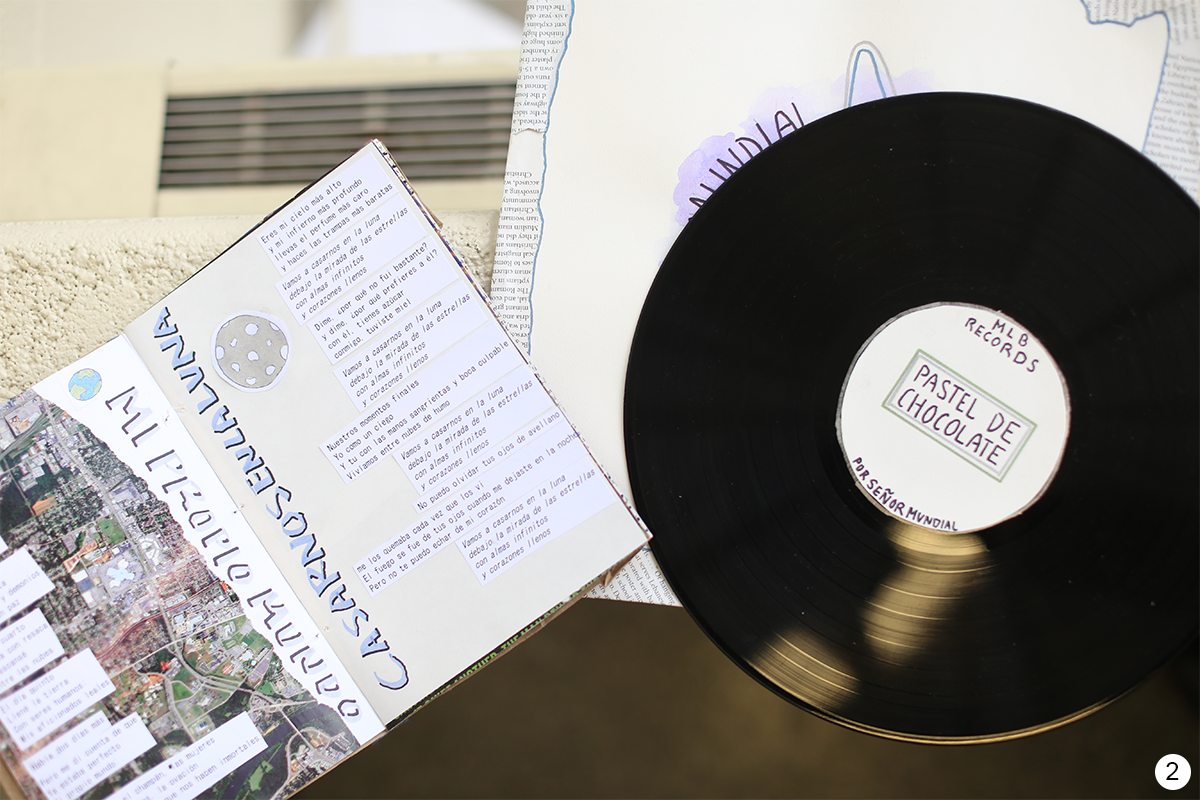

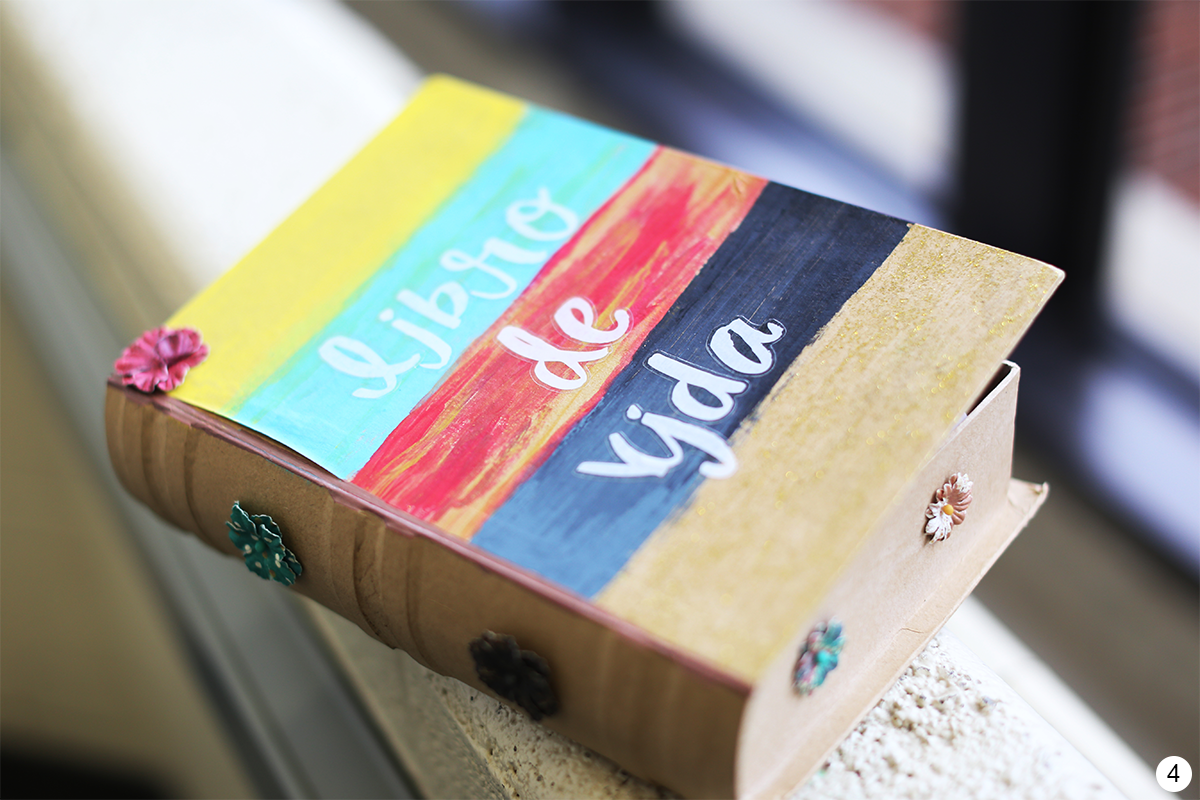

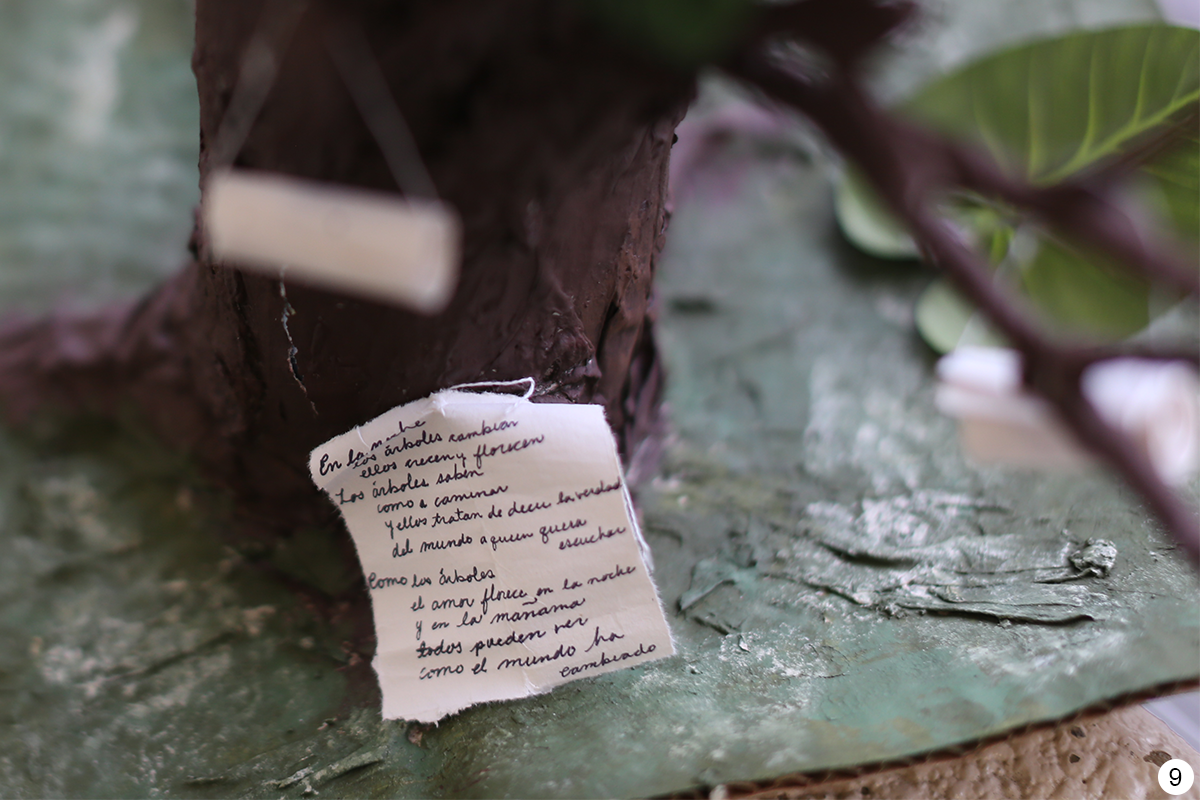

Student artists' books inspired by Cuban collection

Despite the milky gray cast of winter from the window, Shannon Dowd’s office on the fourth floor of the Modern Languages Building is bright with color.

From the top of a bookshelf, blue and magenta petals spill out from a crown of paper flowers, while nearby, the delicate foliage of a papier-mâché tree offers a reminiscent summer green. Alongside these sit an intriguing book-shaped box splashed with sunshiny gold and yellow and red paint; an illustrated vinyl record; and other treasures.

Step closer to these objects crafted by students from Dowd’s recent Spanish poetry workshop, and you may notice something else, too, almost like a secret: tiny poems, tucked into the petals, streaming from the sides of the box, and scribed onto the tightly rolled scrolls that hang, like ornaments, from the tree’s branches.

Poetry is everywhere.

More/LessThe final task bestowed upon her students, Dowd explains, was to pull together different threads of influence from poets or formats explored over the course of the semester — canonical work from eminent Latin American and Spanish writers such as Roberto Bolaño, Gioconda Belli, and Roque Dalton.

“And I’m pleased,” she says, “that so many of them are captivated by the question of form — not limiting themselves to the traditional form of a book.”

One source of inspiration came from an October visit to the Special Collections Research Center, and its collection of Cuban artists’ books.

The collection, mostly comprised of books designed and created by the independent publishing house Ediciones Vigía and its cofounder’s newer imprint, El Fortín, is a perfect study in subverting traditional notions of what a poem or book should look like.

Vigía started in Matanzas, Cuba, in 1985, at a time when all cultural institutions were under control by MINICUT, the Ministry of Culture. The group of artists, writers, and designers involved in Vigía, founded by principal designer Rolando Estévez and fellow poet Alfredo Zaldívar, managed to fly under this radar by crafting poetry books using one borrowed typewriter, an old mimeograph machine, and assorted scavenged supplies sourced during a national paper shortage, such as paper from a local butcher.

The result are striking handmade books — generally no more than 200 copies exist of each — fashioned out of string, fabric, leaves, found paper, and more, with hand coloring, elaborate lettering, and, usually, Estévez’s vibrant illustrations.

Kristine Greive is the curator of this collection.

“I think what people respond to about this work in particular is that [the artists] integrate a lot of found materials into it, and they use materials that feel very approachable,” she says. “There is a spectrum of artist books out there, but the ones that we think of as ‘fine printing’ might come in a beautiful box that's made for it and when you open it up it's all on handmade paper and it’s letterpress printed.

“Those things can be very beautiful, but they can also be intimidating and austere. Vigía was really founded to put the means of production back in people's hands, and to make art accessible locally.”

The library’s collection includes a large, billowing sail that unfurls from a traveler’s knapsack to hang from a real fisherman’s oar; poems hidden within the compartments of a large suitcase; verses painted on planks of wood, and more, all with intricate layers of meaning and metaphor.

“Some people, when they see something like this plank of wood, they're like, ‘How is that a book?’” Greive says. “And I think one of the ways it is a book is that it's intended to be something you have a personal and physical interaction with, as opposed to something that hangs on a wall [in a museum] and is sort of inaccessible to you. It's supposed to be something that you touch and you feel and you have a real connection to. That's part of why people respond so well to this work in general, besides the fact that it's just stunningly beautiful and really creative.”

— Emily Buckler

Pictured: Artists' books created in Shannon Dowd's poetry workshop include work by Hayley Purdy [1]; Natasha Gibbs [2]; Dania Harris [3]; Paige Lombardi [4–5]; Kate Anderson [6–7]; and Tabitha Baker [8–9].

Scholarly internship offers range of opportunities

Growing up in a social justice-oriented family, Meghan Brody originally thought she might attend law school, where she could represent underserved people and effect change in social policies as a public interest lawyer.

But along the way — especially as she began her undergraduate studies in Ann Arbor — Brody began to think about libraries: the ways in which they serve their communities, and the inclusive, accessible programming inherent to the library model.

Now, the history senior plans to attend graduate school in library and information science.

“I changed toward a career in librarianship because I felt like, as a librarian, I [would have] an opportunity to become more involved in a community and create more positive change than were I to be a lawyer,” she says.

To experiment with this concept as an undergraduate, Brody sought out the U-M Library. With its nine locations, the library is one of the largest student employers on campus and maintains a wide range of opportunities, from paid internships to hourly positions where students can serve as gallery attendants, publishing and acquisition assistants, data visualization consultants, digital media technicians, and more.

For Brody, applying to serve as a Michigan Library Scholar was a great way to delve into the real-life projects librarians encounter on a daily basis, specifically tailored to her interests.

“The program was created to provide students the opportunity to work hands-on in a professional environment, build one’s resume practically, further project management skills, and build a foundation for career development,” says Laurie Alexander, associate university librarian for Learning & Teaching. “It is also an opportunity for students to engage with the library in fresh and innovative ways.”

Brody’s project involved developing a “Living Library” program in coordination with Onsite User Services and Outreach Assistant Jasmine Pawlicki, then co-chair of the Library Diversity Council, and Diversity and Inclusion Specialist Jeff Witt. Based on The Human Library, a Living Library event would allow members of the U-M community to be “checked out” for a certain period of time in a designated library space to share personal stories with a guest — all in an effort to foster connections and challenge misconceptions through conversation.

More/Less Currently, the Living Library committee is recruiting people who would like to serve as “books” through U-M’s International Center and Services for Students with Disabilities, with an eye on developing sustainable relationships with participants over time. The framework for the project is based on anti-oppression principles, Pawlicki says, and is very intentional about how it will support and protect its volunteers. Brody says such events, which focus on one-on-one connection and vulnerable conversations, can lead to confronting stereotypes and encouraging empathy. “This is not a transactional conversation — it is meant to be transformational,” Brody explains. “Really, if facilitated correctly, all conversations about something as personal as identity will be impactful for the speaker and the listener. Hearing someone’s story face-to-face certainly encourages empathy, and hopefully that empathy will lead to compassionate action.” Other 2018 Michigan Library Scholars include: Applications for the 2019 program are due Monday, February 25. -Emily Buckler

2018 Michigan Library Scholars and mentors, from top to bottom: Jeff Witt and Meghan Brody; Gabriel Mann and Shevon Desai; Miriam Attal and Jason Imbesi; Kathleen Moriarty and Christopher Dryer

Undergraduates can apply to the Michigan Library Scholars program, which offers paid internships and real-world professional experience via a practical, hands-on project with a global or international focus. All majors welcome.

Work period: May 6–July 26, 2019

Hours: 20–30 per week

Pay rate: $12/hour

Application window: Jan. 18–Feb. 25, 2019

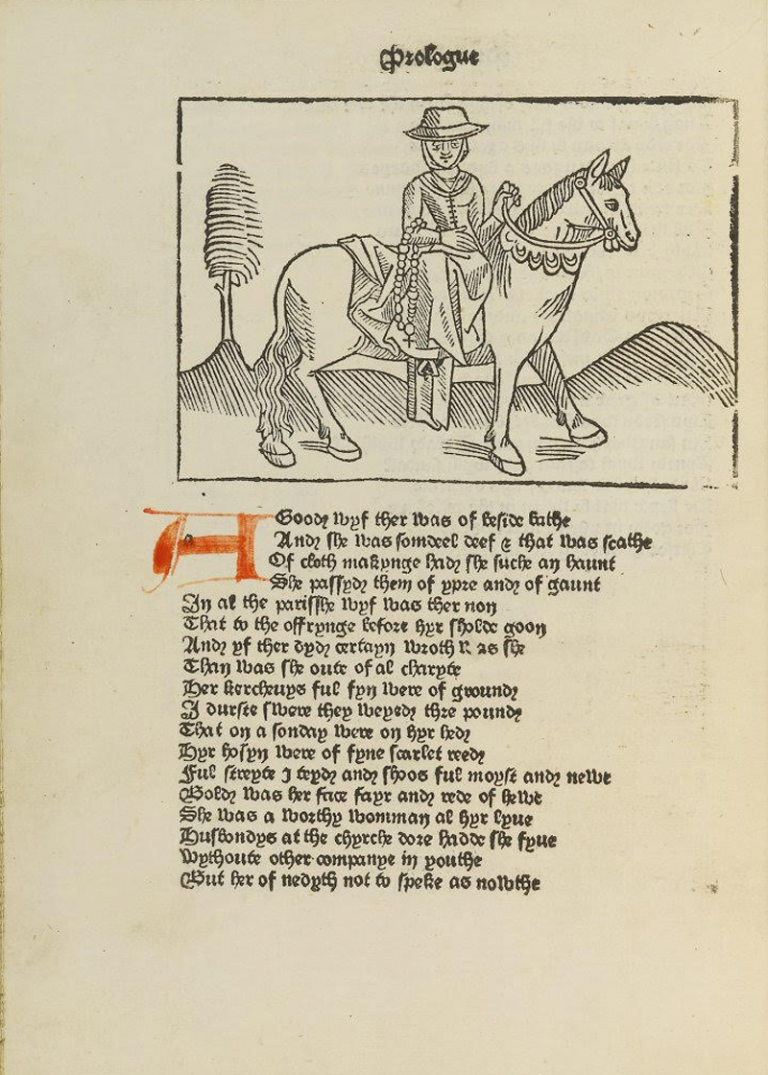

In the Middle English Dictionary, everything old is new again

Let’s get through the awkward question first: why update a dictionary for a language that hasn’t been spoken since the end of the Middle Ages, more than 500 years ago?

Well, one might point out that Middle English is the language of Chaucer, author of The Canterbury Tales, which remains a seminal work in the canon of English literature. Scholars today continue to grapple with unanswered questions about its structure, content, and contemporary dissemination; and readers, whether of the original or a modern rendering, are reminded in some of the bawdier tales that the people of the Middle Ages were every bit as human as we are.

One might also point out that Middle English, foreign as it may seem, is antecedent to the English we write and speak today, and thus remains important to linguists and scholars who seek to answer the many “whys” the English language presents.

One might also point out that the era of Middle English was tumultuous, and that the contours of this tumult remain resonant in our time: social, political, and religious conflict; mass migration; shifts in the role of women within and beyond the domestic sphere; economic disruption unleashed by the introduction of new technologies. There are direct and indirect lines from that period to the present, and to fully understand the lives and events described in the contemporary written record, researchers need access to the language of the time, in all of its nuance.

More/LessAnd one might also point out — as did Paul Schaffner, who’s leading a U-M Library project to comprehensively update the online Middle English Dictionary — that heretofore unstudied texts from the period continue to appear in print, contributing both new words, and novel uses of existing words, to the lexicon. Among them are a popular medical text, thousands of local documents recently published in the Middle English Local Documents database, a dictionary of medical terms that contains hundreds, maybe thousands of terms not previously know to have been part of the Middle English vocabulary, and thousands of artists’ recipes for ink, paint, and dyes that are full of everyday words for artists’ materials.

Not incidentally, this long-awaited update reinvigorates a project with deep roots in the University of Michigan.

The work of seven decades

Work began in earnest on the Middle English Dictionary at the university in 1930, though its origins go back further still, to 19th-century work on the Oxford English Dictionary. (For an enlightening read about the fractious early years of the project, see James Tobin’s War Over Words.) It was an academically prestigious, laborious, and very low-tech affair: early releases — the dictionary was published in segments, sold by subscription, with each individual portion (the term of art is “fascicles”) encompassing a range of letters — were printed from camera-ready typewritten pages.

“For a long time, they actually produced it on two typewriters, one for Roman, one for bold,” Schaffner says, with the first typist leaving blank the necessary spaces for the second. By the time he joined the project as a lexicographer in 1989, they had graduated to a dot-matrix printer, with a font that simulated the typewriter’s for consistency. The last fascicle shipped in 2001 (now produced from laser-printed pages, the typewriter font abandoned), and the Middle English Dictionary was finally complete. That edition, published by the University of Michigan Press, remains in print. For scholars studying the Middle Ages, it was an indispensable resource.

“Completeness,” however, is a chimera to the lexicographer. By the time that last fascicle shipped, there were already thousands of “supplement slips” (notes regarding errors, omissions, citations, etc.) accumulated toward a new edition, as is typical for any dictionary. But the organization that created the Middle English Dictionary had dissolved; there was no plan for a revision or supplement. And the project to bring the dictionary online as the Middle English Compendium (the dictionary along with its associated bibliography and a searchable corpus of Middle English texts), initiated by the library in 1997 with Schaffner brought in to manage, was focused on the then-formidable challenge of translating a print resource into a useful and useable online experience.

A library resource, renewed

The online compendium went live in 2000, and though it offered a few corrections and clarifications, it was meant to serve as an accurate online version the citable, authoritative print version. But Middle English scholarship did not stand still; new texts, new words, new meanings, continued to emerge.

There were many factors that drove Schaffner in 2015 to apply for a National Endowment for the Humanities grant to update the compendium, among them yet-unused dedicated gift dollars, which could serve as matching funds; the technological obsolescence of the crumbling underlying platform; the datedness of the user interface, which presented growing difficulties for each new generation of scholars; and the aforementioned lag between the compendium and relevant scholarly discoveries and publications, to name just a few. But it was those thousands of supplement slips, accumulated over decades and containing a wealth of inaccessible knowledge, that presented both the driving motive and the greatest challenge: Schaffner knew the information was valuable, and that any update seeking to incorporate it would be resource-intensive

Now, with the two-year grant at an end and thanks to the work of Schaffner and others in the library's Digital Content & Collections department, the renewed compendium is online in beta form, with a vastly improved user interface residing on a stable platform that allows for regular updates and ensures the viability of the site for the foreseeable future. On the content side, the dictionary now incorporates quotes and information from those 20,000 supplement slips and from recent editions of Middle English texts that call out words not captured in the dictionary — in effect, crowdsourced additions and corrections. Other improvements include improved linkage to entries in the Oxford English Dictionary and the Dictionary of Old English, and a host of corrections the older platform couldn’t accommodate.

Schaffner is careful to note that this renewal project has no end point; eventually, the beta compendium will go live and the original interface will be retired (the target date is April 2019), and that will mark an important milestone. But built into the team’s work is the creation of a process for ongoing revision — no more waiting half a century (the first fascicle was published in the 1950s) for corrections and updates. From now on, the dictionary and its accompanying resources will both inform and be informed by new linguistic, historical, and literary discoveries.

While Schaffner leaves no doubt that the renewed compendium is an all-around improvement (as confirmed by researchers who have tried the beta version), he’s too much of a scholar to be entirely satisfied. Asked if the new version leaves anything valuable behind, Schaffner mentions the original’s “veneer of authority and comprehensiveness.” Because of the great backlog of additions and corrections and limits on the resources to process them, the updated dictionary contains “much semi-digested material [...], many ‘stub entries’ à la Wikipedia, and many draft additions, all marked as such.” The team prioritized making the material available over preserving a dictionary’s traditionally authoritative stance — “exposing the fact,” Schaffner says, “that the Middle English Dictionary, like every dictionary, is and always was a contingent set of surmises, and a semi-informed work in progress.”

The move away from overstated authority toward authenticity and openness seems to be in keeping with 21st century moods and trends, which are driven and enabled by the technology of our time. And this perhaps echoes another time, hundreds of years ago, when Middle English, the vernacular of the people, began to compete with French and Latin in written works, and when the very first books were produced via the printing press, a new and revolutionary technology.

Among those first printed books was The Canterbury Tales.

— Lynne Raughley

Beyond the library

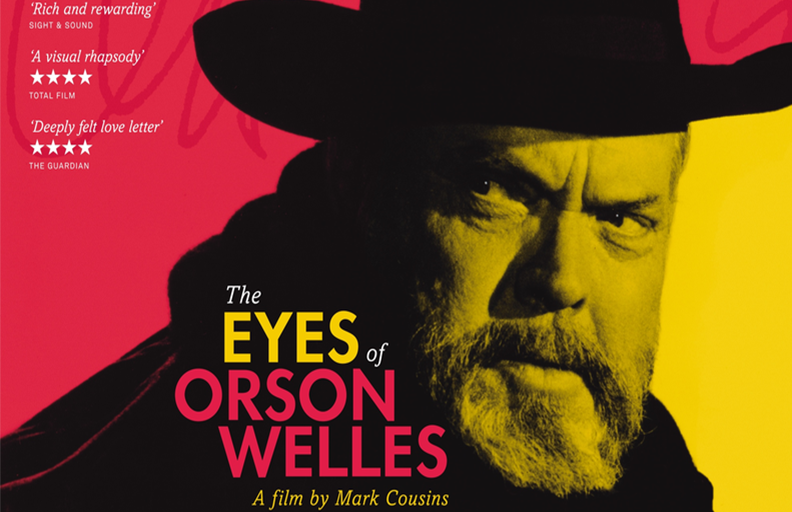

A debut at Cannes, via the library

A film that was a big hit at last summer’s Cannes Film Festival might not have come to be if Film Studies Librarian Philip Hallman hadn’t noticed a tattoo on the arm of producer and director Mark Cousins back in 2016. It depicted a signature, larger than life and unmistakable, much like the man it belonged to — legendary filmmaker Orson Welles.

The tattoo marked Cousins’ lifelong obsession with Welles, and it’s an interest Hallman shares, as curator of the Screen Arts Mavericks & Makers Collection and steward of the largest library collection of Welles materials. When he met Cousins — they were on a panel together at the Traverse City Film Festival — he was in the midst of acquiring additional materials belonging Beatrice Welles, the filmmaker’s daughter, who also attended the festival. Naturally, Hallman introduced them.

Beatrice Welles, it turned out, was familiar with Cousins’ work (“The First Movie,” “The Story of Film: An Odyssey,” and many others); and as an admirer of his work, she encouraged him to make a film about a less-well-known aspect of her father’s work: his visual art.

More/Less"I always wanted to make a documentary about my father’s artwork," she told Wellesnet in 2018. And in Cousins, she was certain she’d found a filmmaker who could do it justice.

Any lingering doubts on Cousins’ part — he wasn’t immediately convinced that he’d be able to say something new about Orson Welles — dissipated quickly. He spent hours looking at vast numbers of Welles’ sketches, drawings, and paintings, including those in the U-M Library and within Beatrice Welles’ private collection, to which he had exclusive access. In an interview with Variety, Cousins says he “started to see in them how [Welles] thought visually. He drew when he was off duty, or relaxing, or upset by work or love. We see those feelings and emotions in his art, but also his sense of composition and form.”

The film, “The Eyes of Orson Welles,” is an intimate portrait, one that Cousins has described as “a letter to a dead dad.” It includes scenes in which Cousins, unseen, explores the drawings, papers, and artifacts that reside within the library’s Orson Welles collections.

Already released to great acclaim in the UK and Ireland, “The Eyes of Orson Welles” is set for a February 2019 theatrical and DVD release in the U.S.

And for those who can’t wait that long for a Welles fix, Netflix is currently streaming the latest, and almost certainly the final, film by Orson Welles, “The Other Side of the Wind.” Shot between 1970–1976 and still unfinished when he died in 1985, the film was finally completed in 2018. It, and the documentary “They’ll Love Me When I’m Dead,” which chronicles Welles’ effort to finish the film (also available on Netflix), relied in part on materials found in the Mavericks & Makers Collection.

— Lynne Raughley

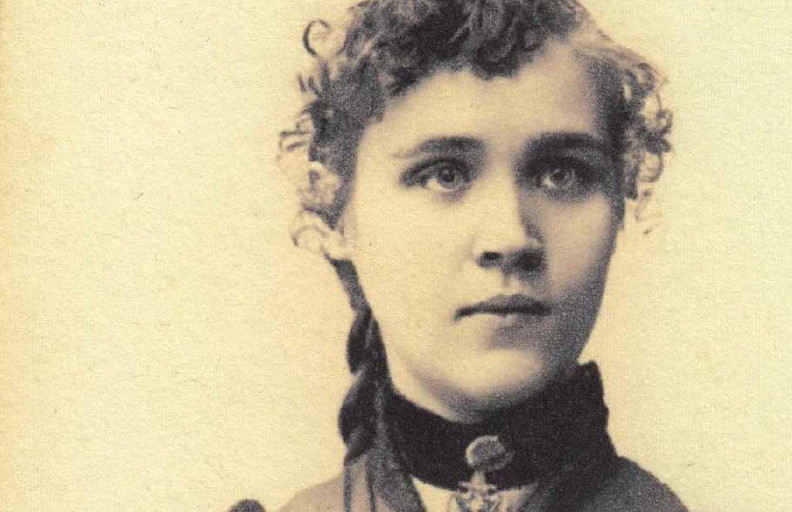

NYT series profiles neglected but “gifted and brilliant” anarchist

A profile of Michigan-born Voltairine de Cleyre, whose papers are archived in the library’s Labadie Collection, was recently featured in The New York Times’ Overlooked obituary series.

Labadie Curator Julie Herrada worked with the Times to provide information and images for the piece on de Cleyre, who was a radical free thinker, feminist, anarchist, and writer who published hundreds of works — lectures, pamphlets, poems, short stories, and more — from the 1800s until her death in 1912.

Although her contemporary Emma Goldman called her the “most gifted and brilliant anarchist woman America has ever produced,” de Cleyre’s work has been largely excluded from the U.S. historical and literary canon.

On identifying herself as a nonviolent anarchist, de Cleyre wrote, in 1909: “This is the time to boldly say, ‘Yes, I believe in the displacement of this system of injustice by a just one; I believe in the end of starvation, exposure, and the crimes caused by them; I believe in the human soul regnant over all laws which man has made or will make; I believe there is no peace now, and there will never be peace, so long as one rules over another.”

In addition to the Labadie Collection’s papers, an examination of de Cleyre’s life and work can be found in Gates of Freedom: Voltairine de Cleyre and the Revolution of the Mind, first published by the University of Michigan Press in 2005. You can read it online via the HathiTrust Digital Library, or use Library Search to find a print copy.

New image collection shows predators and their prey

To investigate the diets of a various snake species, Mike Grundler, a PhD candidate in the Department Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, dissected more than 500 specimens from the U-M Museum of Zoology’s collection of nearly half a million preserved reptile and amphibian specimens — the second largest collection in the world. Images of those specimens, along with the 200 prey items he discovered, are now captured in a new digital image collection (herpetophobiacs beware) that includes metadata on predator species and where and when they were collected.

Grundler’s aim is to discover patterns in the evolution of neotropical snake diets, and the capture and sharing of these high-resolution images and their metadata allows his research to become part of a global network of resources about these creatures and the changes to their ecosystems over time.

This collection has a connection to another digital resource, too. The Herpetology Field Notebooks Collection displays the pages of 286 notebooks kept during the collection of these and other specimens held at the Museum of Zoology. The library’s Digital Content & Collections department anticipates someday linking the predator/prey images to the corresponding entries in these notebooks, some of which include detailed descriptions of field conditions, habitat, and specimens.

Image gallery

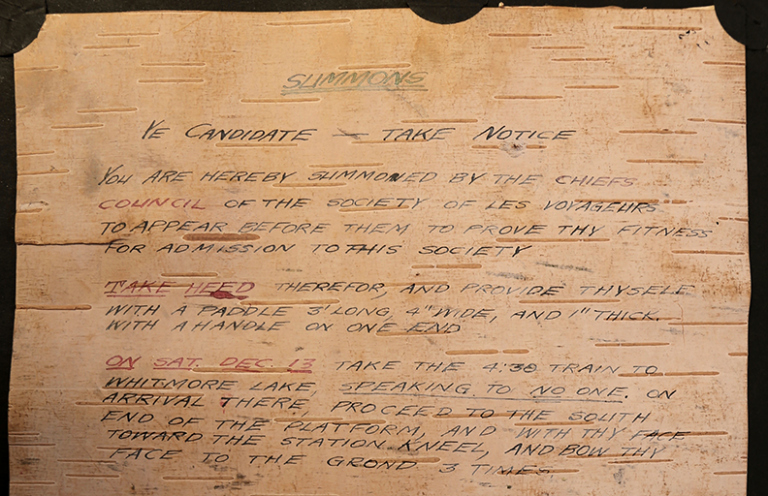

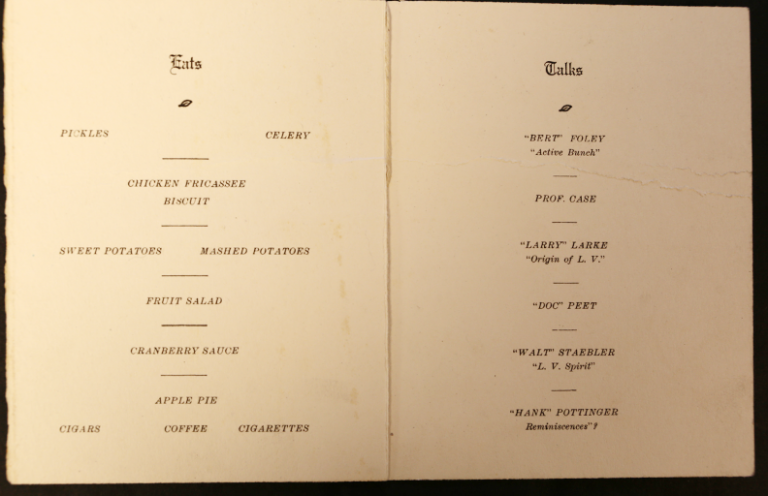

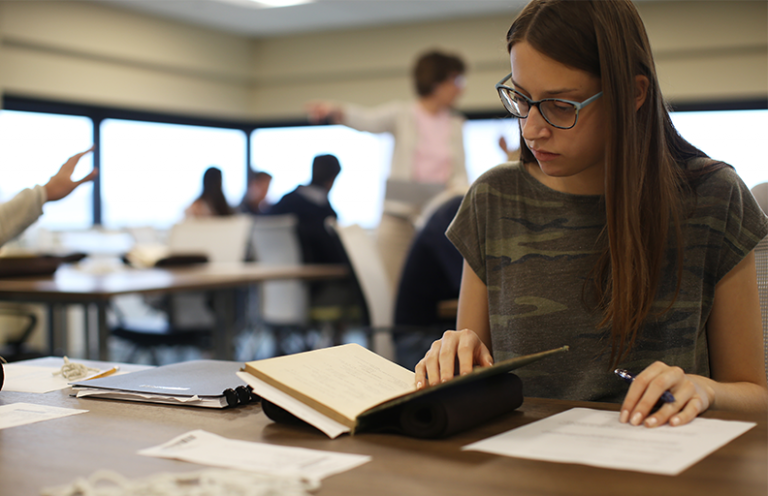

As part of their investigation into changes that have occurred in the university’s food system over time, students in Lisa Young’s first-year seminar traveled to the Bentley Historical Library to explore its unique collection of student scrapbooks from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Tucked inside these scrapbooks — among dance cards and football programs — are menus from special banquets former students had attended, where dishes like veal with cheese, chicken fricassee, mashed potatoes, and coconut cake were popular.

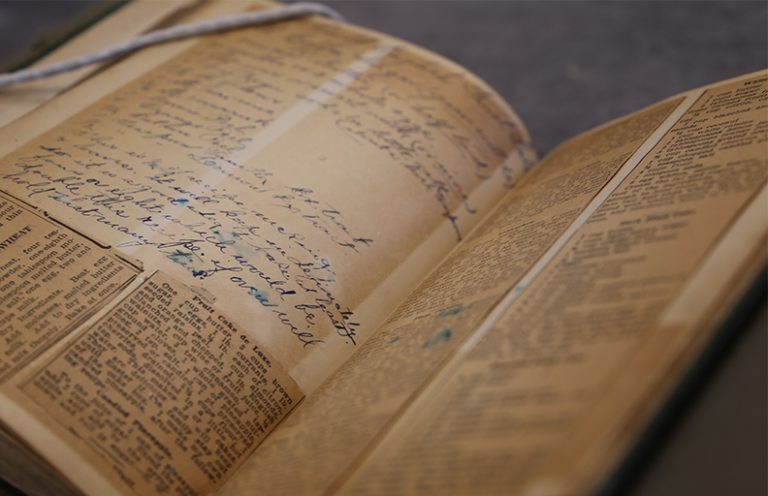

To learn more about how this food was prepared 100 years ago, Young’s class then visited the U-M Library’s Special Collections Research Center, where they examined a variety of cookbooks produced between 1870–1930 from the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive. The archive, shaped by an assemblage of material donated by adjunct curator Jan Longone, contains more than 25,000 items illustrating more than 200 years of culinary life in America.

After the class had selected recipes from the archive that aligned with those century-old menu items, they sent the list to Michigan Dining Chef de Cuisine John Merucci, who recreated the historic dishes with his MDining team and served them to diners in South Quad on select nights at the end of last term.

Learn more about students’ research.

Featured blog post

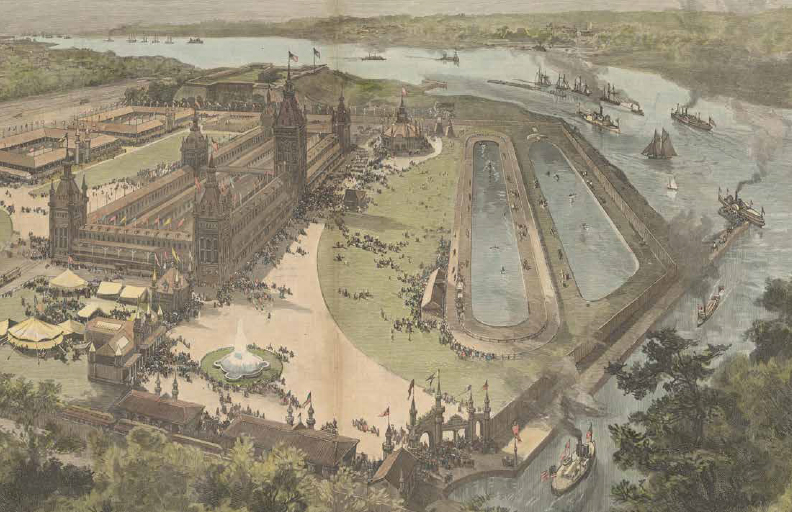

In Merging the Old and the New: Bird’s-Eye Views of America, School of Information graduate student Corey Schmidt writes about his summer internship, during which he cataloged, digitized, and built an interactive display for a collection of artists’ renderings of bird’s eye landscape views from the 19th century — a portal to an art largely lost in the age of photography.

Current & upcoming

Check our Upcoming Library Events on a regular basis and sign up to receive our weekly exhibits & events email. Highlights include ongoing monthly events: Third Thursday Open House in the Clark Library, and Special Collections After Hours in the Special Collections Research Center.

Café Shapiro

Student writers, nominated by their instructors, read their poems and short stories. For many students, Café Shapiro is a first opportunity to read publicly from their creative work. Join us for a reading, or come to all five. Five evenings in February in Bert's Lounge, Shapiro Lobby.

Written Culture of Christian Egypt

See Written Culture of Christian Egypt: Coptic Manuscripts from the University of Michigan Collection in the Audubon Room, Hatcher Gallery | Through February 17

This exhibit features works of Coptic literature from the U-M Library Special Collections Research Center. Preserved by the dry climate of the Egyptian desert (like so many other ancient artifacts), these manuscripts document the transmission of the literary heritage of Egyptian Christians, from its beginnings in the 4th century through the 13th centuries CE.

Sinking Cities

See Sinking Cities: Documenting the realities of climate change in cities around the world in the Clark Library, 2nd floor Hatcher | Through February 28

This multimedia exhibit provides a platform to begin understanding the effects of rising sea levels along the coasts of Indonesia, Bangladesh, The Netherlands, Italy, and the United States. By the end of the century, oceans are predicted to rise between .3 and 2.5 meters, which will result in major flooding in coastal cities around the world. The Sinking Cities Project aims to document this inundation through the stories of residents and the changing landscape of their cities.

Free Poems and Functional Art

See Free Poems and Functional Art: 50 Years of the Alternative Press in the Audubon Room, Hatcher | February 25 through June 3

In 1969, Ann and Ken Mikolowski set up a 1904 letterpress in their home and began The Alternative Press. After getting their start printing free broadsides of poetry, they began a series of experimental mailings: envelopes that included an assortment of bookmarks, broadsides, bumper stickers, and postcards. Along with selections of this work, this exhibit includes correspondence and drafts that offer a behind-the-scenes view of the workings of the press and its associated artists and writers.

Featured Online Exhibit

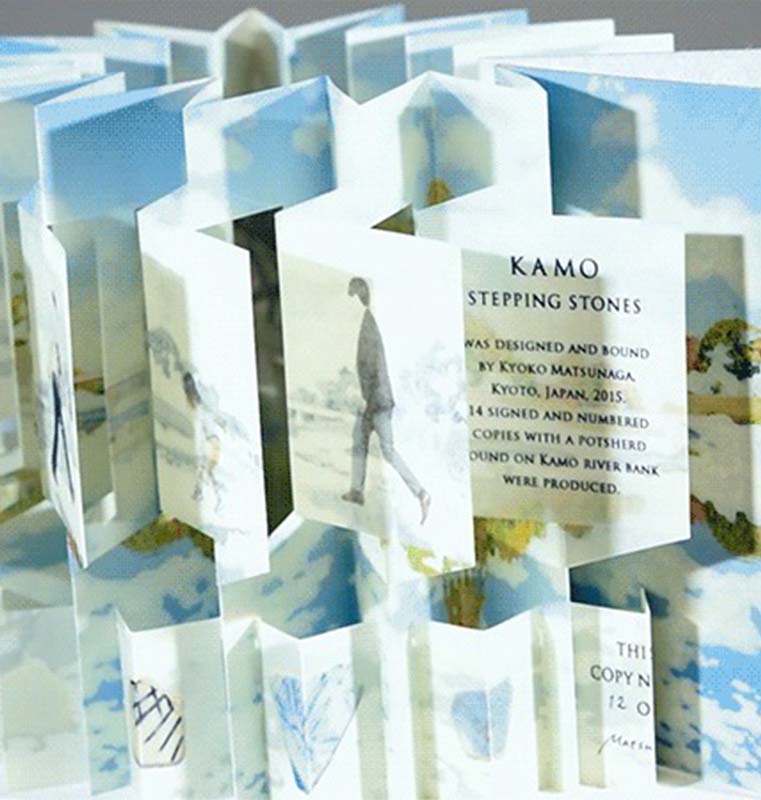

Layered Places: Artists' Books by Kyoko Matsunaga features a close look at three books, each very different in form but all conveying complex ideas about place. The exhibit, curated by undergraduate Maggie Johnson during a Michigan Library Scholars summer internship, features images as well as animated gifs that page through each of the books, offering a fuller sense of the in-person viewing experience.